Paul Birchard writes:

U & Me & Tennessee

has

certainly taken a lot more time than I envisaged when we started

out in June, 2005...! Persistent lack of money leads to delays -

the need to earn money to continue the work takes time away

from editing, rostrum, music - the entire project is forever balancing

on a knife edge - will we get it completed? Or will we all die

first ? (God forbid!) - But frustrating as it is, that's

simply standard operating proceedure in real independent movie-making.

As

Jack O'Brien (Tony Award-winning director of Hairspray)

observed to a tired actor during rehearsals of His Girl Friday

(when I worked with him back in 2003):

"

Well - You wanted to be in the show! "

A

friend asked me recently how I'd managed to maintain my focus

and enthusiasm for U

& Me & Tennessee

over such a long haul ?

I

suppose that boils down to answering this question:

What

does Tennessee Williams mean to me?

Well, first of all, as a young actor discovering Tennessee's work

by grappling with his early one-act plays - The Lady of Larkspur

Lotion,

Mooney's Kid Don't Cry, Something Unspoken  (to

name only three) - fiercely rehearsed by me and my fellow student

actors late at night or in the early morning hours before Charles

Vernon's Acting class in the basement of Royce Hall at

U.C.L.A. - big, challenging roles in bite-sized plays that

we watched one another bring to varying degrees of life......

(to

name only three) - fiercely rehearsed by me and my fellow student

actors late at night or in the early morning hours before Charles

Vernon's Acting class in the basement of Royce Hall at

U.C.L.A. - big, challenging roles in bite-sized plays that

we watched one another bring to varying degrees of life......

If

"a book is a machine to think with," Tennessee's

one-acts are well-crafted, sturdy devices to learn to act

with.

Charles

Vernon, my Scottish Acting teacher, summed up Tennessee's

dramatic method as follows:

"

Poetic Expression of the Sub-Text "

-

and this still seems to me to be entirely apt.

(Some

of Charles's other students included Forrest Whittaker,

Tate Donovan, Ally Sheedy and my dear friend the

late director Charlie Hall.)

The

Glass Menagerie is undoubtedly

a masterpiece, and a powerful reminder that the personal, the

particular is the universal, the political.

During

his lifetime, various pundits remarked that Tenn's plays are not

sufficiently political in their outlook, and he suffered some

rebuke because he did not champion homosexuality more openly in

his work.

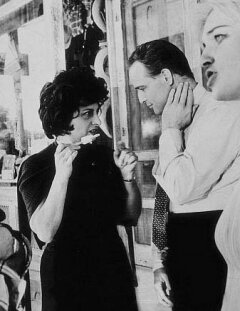

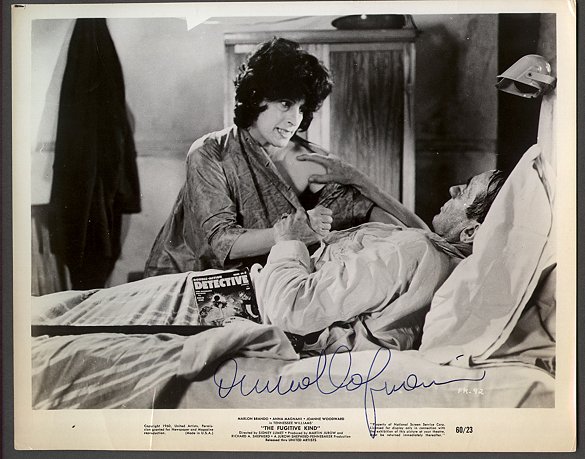

Konrad

Hopkins and I recently saw The Fugitive Kind on the big

screen - directed by Sidney Lumet and written by Tennessee and

Meade Roberts - and it is a really great movie -

very powerful.

There

are minor things in it that one might quibble about ( I would

like to have seen Marlon Brando actually play that guitar

at least once !), but watching it in the context of the ongoing

rape of Iraq by pathologically murderous elements of American

(and other) power, and remembering Vietnam and too much else -

I could clearly see the entire foundation and much of the superstructure

of the death-loving, criminal combine currently in the ascendant,

portrayed in the clearest detail in Tennessee's script - brought

to terrifying life by Victor Jory (Jabe) and R.G. Armstrong

(the Sherrif).

There

are minor things in it that one might quibble about ( I would

like to have seen Marlon Brando actually play that guitar

at least once !), but watching it in the context of the ongoing

rape of Iraq by pathologically murderous elements of American

(and other) power, and remembering Vietnam and too much else -

I could clearly see the entire foundation and much of the superstructure

of the death-loving, criminal combine currently in the ascendant,

portrayed in the clearest detail in Tennessee's script - brought

to terrifying life by Victor Jory (Jabe) and R.G. Armstrong

(the Sherrif).

As

Tenn wrote in his introduction to A Streetcar Named Desire:

"I think the problem

that we should apply ourselves to is simply one of survival.

I mean actual, physical survival !"

Shot

in the late 1950's, Anna Magnani's smouldering, fiery Lady

- Marlon Brando's restrained, reflective Val, Joanne

Woodward's disengaged, alienated Carol all point toward

the future - now - when Americans would need to

realize that we are but one nation among many - that all people

are connected - that we must repudiate deliberate cruelty and

those who practice it (whatever their momentary, specious justifications

for doing so).

The

central challenge of our time is to make war spiritually

on the ingrained attitudes that precipitate most of the suffering

we endure because of cold-hearted, callous people of the type

Tenn clearly portrayed in Jabe Torrance and the Sherrif

in The Fugitive Kind.

For

me, as I've come to think deeply about him during the making of

this movie, it's obvious that Tennessee understood and waged

this spiritual battle, with might and main, over many decades.

In

his work.

Tennessee

fought the good fight in his work.

But

in his personal life, Tennessee was certainly capable of deliberate

cruelty...He was candid about some of it. A lot of it he probably

just forgot.

But

in his personal life, Tennessee was certainly capable of deliberate

cruelty...He was candid about some of it. A lot of it he probably

just forgot.

As

he himself admitted, he was both Blanche and Stanley.

U & Me & Tennessee

is important

because we do not avoid this paradox in Tenn's nature. The impact

of his complex, contradictory personality on Konrad Hopkins is

the very subject of the film. As Konrad makes clear, Tennessee

was capable of being extremely generous, delightful, kind - but

he was also cruel - if not sadistic - cold, thoughtless and self-obsessed.

But

what's remarkable to me - wonderful - about Tennessee is

that even in his cruelty he could impart priceless lessons in

the art of living - Konrad certainly feels this now, though it

took many, many years for him to arrive at this understanding.

But

what's remarkable to me - wonderful - about Tennessee is

that even in his cruelty he could impart priceless lessons in

the art of living - Konrad certainly feels this now, though it

took many, many years for him to arrive at this understanding.

Finally,

the reason we can still make interesting work about Tenn

- nearly twenty-five years after his death - is

not only because of his piercing intelligence, nor what even a

trenchant critic like Frank Rich had to acknowledge was Tennessee's

almost unobstructed channel to the collective unconscious - nor

is it due to his notorious lifestyle, chronicled in his Memoirs

and Notebooks and by others.

It

isn't even because he produced so many masterpieces - A Streetcar

Named Desire, The Glass Menagerie, Summer and Smoke, Sweet Bird

of Youth, and so many other memorable, arresting plays, movie

scripts and stories.

No.

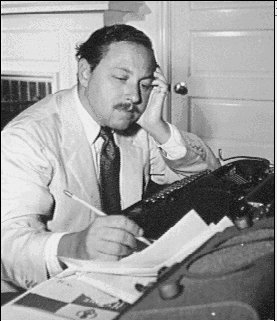

The reason Tennessee Williams is still news, still evokes curiosity

and avid interest is because of his unquenchable committment to

his work - to working every day no matter

what.

Dotson

Rader has written a wonderful book about his close friend:

Tennessee Williams - A Cry of the Heart. In Britain it

was subtitled "An Intimate Memoir" and it certainly

is that.

Dotson

writes:

"I

asked him why he worked every day. I have known a lot of writers

who claim to work every day - I've even made that preposterous

avowal - but Tennessee is the only writer who ever actually

did."

Tenn

replies:

"I

try to work every day, baby, because you have no refuge but

writing. None. When you're going through a period of unhappiness,

a broken love affair, the death of someone you love, or some

other disorder in your life, then you have no refuge but writing...Could

you live without writing, baby? I couldn't...if my work is interrupted

I'm like a raging tiger."

95%

of life is showing up. Tennessee showed up virtually every day

of his life - and worked hard.

(It's interesting to note that JAMES T. FARRELL, the

other writer Konrad Hopkins knew well, also worked

incredibly hard - writing twenty to thirty pages a day,

most of the time! Konrad edited three of Farrell's

books for him. Unlike Tennessee, Farrell had no qualms about

allowing another's editorial sense to shape his work.

Konrad still writes about 1,000 words a day himself !)

If you want to hear Tennessee's voice, you might

get ahold of a copy of the new edition of his Collected

Poems. New Directions books have included a CD of Tenn

reciting some of the poems !

National Public Radio also featured an

interesting piece a few years back, still available on the web,

about some old cardboard phonograph records made in a penny arcade

in New Orleans by Tennessee and his then companion Pancho, which

had been lying at the bottom of a trunk full of stuff Tenn had

left at Donald Windham's place - It's worth a listen.

There is a lot more I'd like to say - but - long

story short ? -

When I began work on U

& Me & Tennessee I was prepared to believe that

Tennessee had behaved very badly toward Konrad Hopkins in particular,

and by implication and recorded fact, many other people as well.

As I've read and thought more deeply about him

over these past two years, I've come to have a more balanced view

of Tennessee Williams, and a respect, an admiration for Mr. Williams's

unceasing artistic efforts and achievements has been born in me,

which continues, each day, to grow stronger and deeper.